|

| Looks like an Orange Line? Maybe not. (Image: Jeremiah Cox/subwaynut.com) |

The actual name of the Chicago Transit Authority’s secret train line is still up for debate. Other candidates include “Brorange”, "Orangown", or hopefully a more appealing combination of “brown” and “orange” you can devise.

Believe it. CTA’s nine true lines consist of Red, Blue, Brown, Orange, Green, Pink, Purple, Yellow, and Brownge.

Its existence is due to creative problem-solving by service planners at the CTA. It became necessary due to exploding Brown Line ridership in the 1990s and 2000s, which sparked the 2006–09 Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project. The project completely rebuilt 16 of the line’s 19 non-Loop stations to bring them up to modern standards--the entire line was built in 1907 or earlier, and many stations hadn’t seen major investment since.

It also extended platform lengths to run 8-car trains, which hadn’t ever been possible on the Brown Line. The CTA’s other most congested lines, the Red and Blue, had sworn by 8-car trains for years. The first 8-car Brown Line trains started running in March 2008, significantly increasing capacity.

But it still wasn’t enough to keep up with demand. And the CTA couldn’t run any more trains because the schedule had already maxed out the available cars at Kimball Yard, a relatively tiny plot of land that houses Brown Line trains amidst a dense residential Albany Park.

The only option left for the CTA was to pull trains from another line’s yard each day and send them up the Brown Line, and the Orange Line was a natural fit. Not only did the Orange’s Midway Yard have excess capacity, the two lines are operationally similar in length (Brown, 11.4 miles; Orange, 12.5 miles) and run time (around 30 minutes each way), and already entered the Loop on opposite ends, so the transition would be relatively natural. If anything, they almost appear to be North and South Side counterparts on the system map.

Not to be outdone, Chicago commuter railroad Metra features a secret line of its own, in addition to the 11 it normally operates. By “line”, in this case we’re looking at just a single weekday train, in one direction.

The train in question begins on Metra’s North Central Service (NCS) line, its second-least patronized line with under 6,000 riders daily. (Metra’s busiest, the BNSF Line to Aurora, serves over ten times as many.) However, the NCS provides 10 valuable weekday-only roundtrips from and to Antioch, Illinois, a 14,000-resident suburb which borders Wisconsin and is literally closer to downtown Milwaukee than downtown Chicago.

The standard 52.9-mile trip from Antioch to Union Station takes 1 hour and 35 minutes. The trains run south through Rosemont just east of O’Hare before merging with the much busier Milwaukee District-West (MD-W) Line at Franklin Park, turning east toward downtown. NCS trains skip a number of lightly-used Metra stations in the city, but on the longer, suburban portion, almost all trains make all stops. North of O’Hare, no stops at all are skipped. The lack of traditional Metra express train service is likely directly correlated to the lower total number of trips that serve this route.

However, the last train of the night out of Antioch, #120 departing at 7:02pm, makes the run into downtown in 1 hour, 16 minutes, without running express on the NCS. How?

The most likely scenario, however, seems to be high demand Metra had recognized for a reverse-commute evening express from Libertyville and Lake Forest. Earlier this year, Metra added even more reverse commute service to the MD-N, partially funded by a highly-motivated Lake County economic development group. Bumping one train over from the NCS may be an easy way to assist with this service.

Let’s just go with the Antioch Express, seeing as it is the only true express train on the NCS. And for that presumably limited number of reverse commuters from Antioch, Lake Villa, Round Lake Beach, Grayslake, Libertyville, and Lake Forest that benefit from it, bully for you.

Thus, the Brownge Line and the Antioch Express. You’ll never see those names on a timetable, but if you know when and where to look, you’ll find them in operation, each and every weekday. Even if you don’t know where to look, if you commute on the Brown, Orange, NCS, or MD-N lines, watch your train’s path closely--you might just be on one.

Its existence, meanwhile, is an operational fact, even if it's not marketed as such. As you might be able to tell by now, the line is a combination of the Brown and Orange Lines.

Unless you’re an early morning Orange Line commuter, morning Brown Line commuter, or have a insatiable desire for random CTA knowledge similar to this writer's, you’re probably unfamiliar with the unbeloved Brownge.

Unless you’re an early morning Orange Line commuter, morning Brown Line commuter, or have a insatiable desire for random CTA knowledge similar to this writer's, you’re probably unfamiliar with the unbeloved Brownge.

|

| Current weekday Orange Line schedule. Note the six trips marked “K” for Kimball-bound (the Brown Line’s terminus), exposing them as Brownge. |

Six Brownge trains run every weekday, each departing from Midway Airport between 6:00 and 6:49am. They masquerade as normal Orange Line trains to the Loop. There, they suddenly become Brown Line trains and, instead of looping around and heading back to Midway, only complete half of the Loop before heading north along the Brown Line.

|

| Current Brown Line weekday schedule. Note the subsequent six trips marked “M” for Midway-bound, the southbound return of the Brownges. |

They reach the end of the Brown Line at Kimball, where they turn around and start a new Brown Line run to downtown. These depart Kimball between 7:23 and 8:13am. Upon entry to the Loop, however, they again turn Orange, and exit the Loop prematurely to head south to Midway Airport. This pattern does not repeat during the evening rush.

Believe it. CTA’s nine true lines consist of Red, Blue, Brown, Orange, Green, Pink, Purple, Yellow, and Brownge.

Its existence is due to creative problem-solving by service planners at the CTA. It became necessary due to exploding Brown Line ridership in the 1990s and 2000s, which sparked the 2006–09 Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project. The project completely rebuilt 16 of the line’s 19 non-Loop stations to bring them up to modern standards--the entire line was built in 1907 or earlier, and many stations hadn’t seen major investment since.

It also extended platform lengths to run 8-car trains, which hadn’t ever been possible on the Brown Line. The CTA’s other most congested lines, the Red and Blue, had sworn by 8-car trains for years. The first 8-car Brown Line trains started running in March 2008, significantly increasing capacity.

But it still wasn’t enough to keep up with demand. And the CTA couldn’t run any more trains because the schedule had already maxed out the available cars at Kimball Yard, a relatively tiny plot of land that houses Brown Line trains amidst a dense residential Albany Park.

The only option left for the CTA was to pull trains from another line’s yard each day and send them up the Brown Line, and the Orange Line was a natural fit. Not only did the Orange’s Midway Yard have excess capacity, the two lines are operationally similar in length (Brown, 11.4 miles; Orange, 12.5 miles) and run time (around 30 minutes each way), and already entered the Loop on opposite ends, so the transition would be relatively natural. If anything, they almost appear to be North and South Side counterparts on the system map.

Hence, the birth of the Brownge Line, likely circa 2009. It represents the only through North Side-South Side service other than the Red Line. Between the six northbound surplus-capacity Orange Line runs and six southbound max-capacity Brown Line runs, it’s entirely possible these trains are serving 3,000–5,000 riders per day. That places it not far behind the Yellow Line’s average ridership for an entire weekday.

The CTA does not outwardly mention the existence of these trains, probably so as to avoid confusion, but they are well-equipped in communicating them. CTA’s Train Tracker displays on the platforms and your electronic device of choice do a great job of denoting trains as “Loop, Midway” or “Loop, Kimball” trains.

The CTA does not outwardly mention the existence of these trains, probably so as to avoid confusion, but they are well-equipped in communicating them. CTA’s Train Tracker displays on the platforms and your electronic device of choice do a great job of denoting trains as “Loop, Midway” or “Loop, Kimball” trains.

The trains themselves cannot do this, however. Train operators do announce its imminent color change as the trains prepare to enter the Loop, giving the unenlightened an opportunity to get off and wait for a monochrome train. The only other thing operators can do is to mark their train’s final destination much earlier, which seems to be happening more often recently. This has the benefit of alerting those in the know, although completely befuddling everyone else.

Imagine a southbound train marked as a Midway-bound Orange Line pulling into Southport Brown Line station during morning rush hour. If you’ve been acquainted with the Brownge, you’ll board it confidently. If not, you’re wondering, is this an erroneously marked train, a schmetically misguided train, an out of service train, or a ghost train?

You weren’t expecting this spooky scene on your morning commute. You were just hoping to get downtown early enough to stop at Do-Rite Donuts before your morning meeting. The uninformed must choose between waiting for the next Brown Line and possibly forgoing the double chocolate glazed, or gambling with the transit gods in hoping this train will get them where they’re going.

The CTA leveraging its rail infrastructure in unique ways is nothing new, however, and it’s important to differentiate the Brownge Line. Whether due to planned maintenance work, capital projects, or service disruptions, the agency (as with any transit agency of its size worldwide) has a long history of temporary line reroutes or cuts. If it's for planned work, these take place primarily on evenings and weekends so as to inconvenience less riders. Some recent reroute patterns include:

You weren’t expecting this spooky scene on your morning commute. You were just hoping to get downtown early enough to stop at Do-Rite Donuts before your morning meeting. The uninformed must choose between waiting for the next Brown Line and possibly forgoing the double chocolate glazed, or gambling with the transit gods in hoping this train will get them where they’re going.

The CTA leveraging its rail infrastructure in unique ways is nothing new, however, and it’s important to differentiate the Brownge Line. Whether due to planned maintenance work, capital projects, or service disruptions, the agency (as with any transit agency of its size worldwide) has a long history of temporary line reroutes or cuts. If it's for planned work, these take place primarily on evenings and weekends so as to inconvenience less riders. Some recent reroute patterns include:

- Sending Red Line trains “up top” in bypassing the State St Subway for the elevated tracks, through the Loop, between Chinatown and Lincoln Park

- Sending Red Line trains down the Green Line elevated on the South Side, done for the Red Line South’s 2013 complete reconstruction and again over the last few years for the new 95th St terminal construction

- Closing one half of the Loop on a weekend, rerouting numerous lines

- Sending Pink Line trains onto the Blue in the median of the Eisenhower Expressway, as a shuttle service to connect with the Blue for downtown service

Not to be outdone, Chicago commuter railroad Metra features a secret line of its own, in addition to the 11 it normally operates. By “line”, in this case we’re looking at just a single weekday train, in one direction.

The train in question begins on Metra’s North Central Service (NCS) line, its second-least patronized line with under 6,000 riders daily. (Metra’s busiest, the BNSF Line to Aurora, serves over ten times as many.) However, the NCS provides 10 valuable weekday-only roundtrips from and to Antioch, Illinois, a 14,000-resident suburb which borders Wisconsin and is literally closer to downtown Milwaukee than downtown Chicago.

The standard 52.9-mile trip from Antioch to Union Station takes 1 hour and 35 minutes. The trains run south through Rosemont just east of O’Hare before merging with the much busier Milwaukee District-West (MD-W) Line at Franklin Park, turning east toward downtown. NCS trains skip a number of lightly-used Metra stations in the city, but on the longer, suburban portion, almost all trains make all stops. North of O’Hare, no stops at all are skipped. The lack of traditional Metra express train service is likely directly correlated to the lower total number of trips that serve this route.

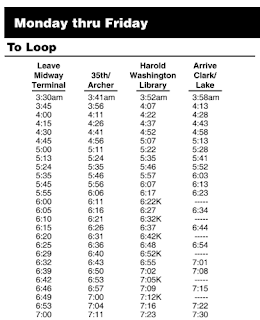

However, the last train of the night out of Antioch, #120 departing at 7:02pm, makes the run into downtown in 1 hour, 16 minutes, without running express on the NCS. How?

It accomplishes this by completely leaving the NCS line for the Milwaukee District-North (MD-N) line, via a crossing in Libertyville. It then does run express to Union Station, stopping in Libertyville and Lake Forest before skipping 13 MD-N stations.

The most likely scenario, however, seems to be high demand Metra had recognized for a reverse-commute evening express from Libertyville and Lake Forest. Earlier this year, Metra added even more reverse commute service to the MD-N, partially funded by a highly-motivated Lake County economic development group. Bumping one train over from the NCS may be an easy way to assist with this service.

Let’s just go with the Antioch Express, seeing as it is the only true express train on the NCS. And for that presumably limited number of reverse commuters from Antioch, Lake Villa, Round Lake Beach, Grayslake, Libertyville, and Lake Forest that benefit from it, bully for you.

Thus, the Brownge Line and the Antioch Express. You’ll never see those names on a timetable, but if you know when and where to look, you’ll find them in operation, each and every weekday. Even if you don’t know where to look, if you commute on the Brown, Orange, NCS, or MD-N lines, watch your train’s path closely--you might just be on one.