In keeping its "legacy" rail network intact, the CTA has rehabbed many rail stations handsomely over the past few decades. Which stations should be next?

|

| Sheridan station on the Red Line. (Image: David Wilson/Flickr) |

In recent decades, the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) has heavily prioritized maintaining its sizable rail transit system over expanding it.

This approach makes sense: as one of few "legacy" urban rail systems in the United States, and one that expanded greatly over the course of a century-plus, there's a lot to maintain. The CTA's 146 rail stations are the second-most among US rapid transit systems, its 103 track miles the fourth-most.

The emphasis on maintenance has served the network well. A strong majority of stations across the system, and often the tracks that serve them, have been significantly rehabilitated within the past 30 years. More lines and stations are still to come.

Today, the system's overall performance, as well as some of the completed line and station reconstruction projects, are often cited as aspirational case studies in other cities. And with over 225 million riders in 2018 (the US' second-most), it's clear that amid flaws and limitations, the CTA's rail network continues to be an irreplaceable asset to city life in Chicago.

But again, there's a lot to maintain. Some branches and stations have been left behind. Some have improvement plans funded and ready to go, such as the north Red Line. Others have unfunded plans stuck on the drawing board, or no plans at all.

Let's take a look at a few of the neglected stations that could use a bump--we'll exclude those currently under rehab or funded for one soon.

State/Lake (Loop: Brown, Green, Orange, Pink, and Purple Lines)

|

| Narrow platforms at State/Lake, the fifth-busiest CTA station by 2018 weekday ridership, serving five lines. (Image: Adam Moss) |

The main culprits here are two dangerously skinny platforms. The platform gets especially narrow (sometimes only one or two standees wide) near the entrance turnstiles, so rush hour crowds quickly become problematic. And as a prime station to access downtown attractions, there is often a good proportion of tourists and irregular riders to make things even more interesting.

The south/Inner Loop platform, which serves the Orange, Pink, and Purple lines, as well as 63rd St-bound Green Line trains, was expanded slightly in 2016 in somewhat of a spontaneous project in response to extreme crowding.

|

| State/Lake is one of Chicago's iconic downtown "L" stations, although this is much more true in location and patronage than in practicality. (Image: Jim Pearson Photography) |

Still, that limited expansion was a temporary fix, and ridership here has grown rapidly--a 36% increase between 2010 and 2018, to over 12,000 boardings per average weekday.

Recognizing the issue, the CTA announced in 2017 that it had received a federal engineering grant to begin the process of completely rebuilding the station. This news was widely reported, especially considering how much of an upgrade the new Washington/Wabash station, one station over on the Loop, has proven.

However, there has been remarkably little mention of it since. The CTA President's 220-page budget recommendations for FY2019 made zero mention of it, and it is not listed on the System Improvement Projects page of the website.

Sheridan (Red Line)

|

| The Sheridan station in Lakeview East, which saw over 5,000 boardings on the average 2018 weekday. (Image: Jeremiah Cox/subwaynut.com) |

All of this can't come a moment too soon for the rail system's busiest branch. But there is one glaring exception, a dilapidated station that seems likely to remain so for some time: Sheridan. Here you'll find cramped stairs and thin wooden platforms squished between active local and express tracks. While the CTA has surely made minor cosmetic updates over the years, the station is largely untouched since a 1930 renovation.

A 2017 Chicago Tribune reader poll voted Sheridan the worst station in the system.

It is not included in the first phase of the Red/Purple Modernization (RPM) project that will soon upgrade most of its neighbors to the north, and to date there haven't been any rumblings of a Sheridan station-specific project either.

In the Tribune reader poll article, CTA spokesman Brian Steele noted Sheridan could be part of the unfunded RPM Phase Two, which I could conservatively estimate will wrap up in the year 2104. But when you look at the station's environment, you can see how even if they revisit Sheridan for Phase Two, the CTA might struggle to decide on a solution.

|

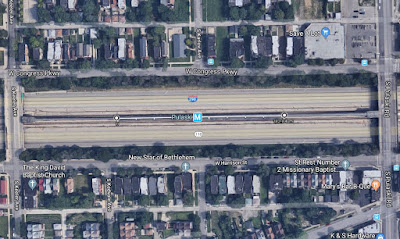

| The Sheridan station's layout on an S-curve, surrounded by dense and valuable private property on all sides, makes any rehabilitation and realignment problematic. (Image: Google Maps satellite) |

Now, it will make for the CTA's most complex station renovation in recent memory. The existing platform width is not up to modern safety standards, let alone a width that would allow for elevators on both platforms, which would be compulsory as part of any rehab.

Widening platforms that are sandwiched between tracks means relocating those tracks, causing service disruptions presumably for multiple years, as well as expanding the overall right-of-way width. As you can see in the satellite image, the S-curve structure passes within inches of private property on all sides. Acquiring some or all of these properties would be expensive and controversial, and it still would only widen the S-curve, not straighten it out.

|

| The cage-like stairs to the Sheridan platforms. (Image: Nandana N/Yelp) |

The only other option would be a short subway between the Addison and Wilson stations, tunneling deep enough to avoid building foundations as it would not be following the street grid. This subway with one station (to replace Sheridan) would be less than a mile, yet it would still cost in the billions.

The bottom line is, as decrepit as it is, don't hold your breath on a Sheridan rebuild. And it is the complexity of the S-curve that makes this a real "all or nothing" situation, because it's nearly impossible to make any meaningful half-measure improvements in the meantime.

Clinton & LaSalle (Blue Line)

|

| LaSalle station. (Image: Cassandra Roman) |

Designed in the 1930s and opened in 1951, the main eight-station Blue Line subway travels from the Division station in Wicker Park, through downtown, and back west through the Clinton station in the West Loop. Most of these eight stations are criminal offenders--only the Clark/Lake and Jackson stations have truly been retrofitted to modern design standards and signage. But let's excuse Division, Chicago, and Grand, as the CTA's Your New Blue program just began significant renovations on those. In downtown, the Washington and Monroe stations are very busy and seem slightly better maintained.

|

| This wonderful streetscape under the Eisenhower awaits you upon exiting Clinton. Heading to Union Station? You'll need to schlep a few blocks north. (Image: Timothy Hamlett) |

The LaSalle station is useful for connecting with Metra's LaSalle Street Station directly above, home of the busy Rock Island line to Joliet, but curiously there has never been a direct connection between the stations.

|

| The deepest underground station in the "L" system, Clinton is also the only one exclusively accessible by escalator. (Image: Christian Wietholt) |

Clinton is sadly the CTA's strongest claim of a rail connection to Union Station, which is over two blocks away with no direct connection. That's a far cry from the direct subway connections found within the grand rail terminals of New York City, Washington DC, and even Los Angeles.

|

| The upcoming Forest Park branch revamp includes plans for improving Clinton's usefulness. (Image: 2017 CTA Forest Park Vision Study) |

Oak Park (Blue Line)

|

| The Oak Park station is between the Eisenhower Expressway and freight rail tracks, in an open cut below the street grid.(Image: Hans Goeckner) |

Most station platforms on this branch are surprisingly narrow, especially given that the concurrent planning with the expressway means more space to them easily could have been devoted.

More problematic, though, is that like most expressway median transit stations, they are not pleasant to wait within (they are open to the elements and their soundtrack is that of the "expressway roar" variety) or walk to (expressway bridges, ramps, and general infrastructure are not generally pedestrian-friendly).

The Forest Park branch stations exacerbate this issue with long, skinny access ramps that connect stations with the street grid above. The theory was that instead of building stations under a major street for direct access, build stations in between two streets, with ramps up to both, thereby spreading walkable station access to more people.

Tangibly, the ramps add to the distance it takes to reach the platform (as opposed to just heading down a staircase from the street entrance), which limits the number of residents and businesses within any certain walkshed.

The Forest Park branch of the Blue Line, originally called the Congress line, was one of the first in the nation to feature stations in the median of an expressway, then considered an innovative idea. While such highway median stations have been built in a handful of other US cities since, the "double-sided access ramps" concept did not catch on. Even "L" lines later built in the medians of the Dan Ryan and Kennedy expressways did not feature entrance ramps.

|

| The infamous East Ave entrance catwalk at the Oak Park (Blue) station. (Image: zol87/Flickriver) |

How do we fix the "entrance ramps" and general unwalkability of these expressway transit stations? We will find out what the CTA has in mind when the project to renovate this line is finally announced soon.

Funding could be an entirely separate challenge. But for what's it's worth, the CTA has drawn up some transformative ideas in the Vision Study.

Main & Dempster (Purple Line)

|

| Dempster station on the Purple Line, which looks here in 2018 almost exactly how it did in 1910. (Image: Aaron Rogers) |

The same can mostly be said for Foster, Noyes, and Central, three other Purple Line stations further up the branch. But these three are remarkably unchanged since their elevation in 1930, making them a youthful 90 years untouched, compared to 110 for Main and Dempster.

|

| Dempster and Main's station houses, which are very smiliar, truly feel like those of another time. (Image: Chicago Transit Authority) |

Part of the reason for the lack of investment in these two stations has to be their lower ridership numbers. This makes them a lower priority, so much so that Dempster was one of 23 stations slated to close in 1991 due to a CTA budget crisis. However, the crisis was averted and Dempster stayed open.

|

| The Main station's walkways to the platform. Of the CTA's 146 station rail system, this style is not seen anywhere other than these aging Purple Line stations. (Image: Jeremiah Cox/subwaynut.com) |